Naomi Lubrich, Alessandro Fabri, Iudaeus Medicus, 1803

Alessandro Fabri, Iudaeus Medicus, 1593

Delacroix, Noces juives, 1841, Louvre

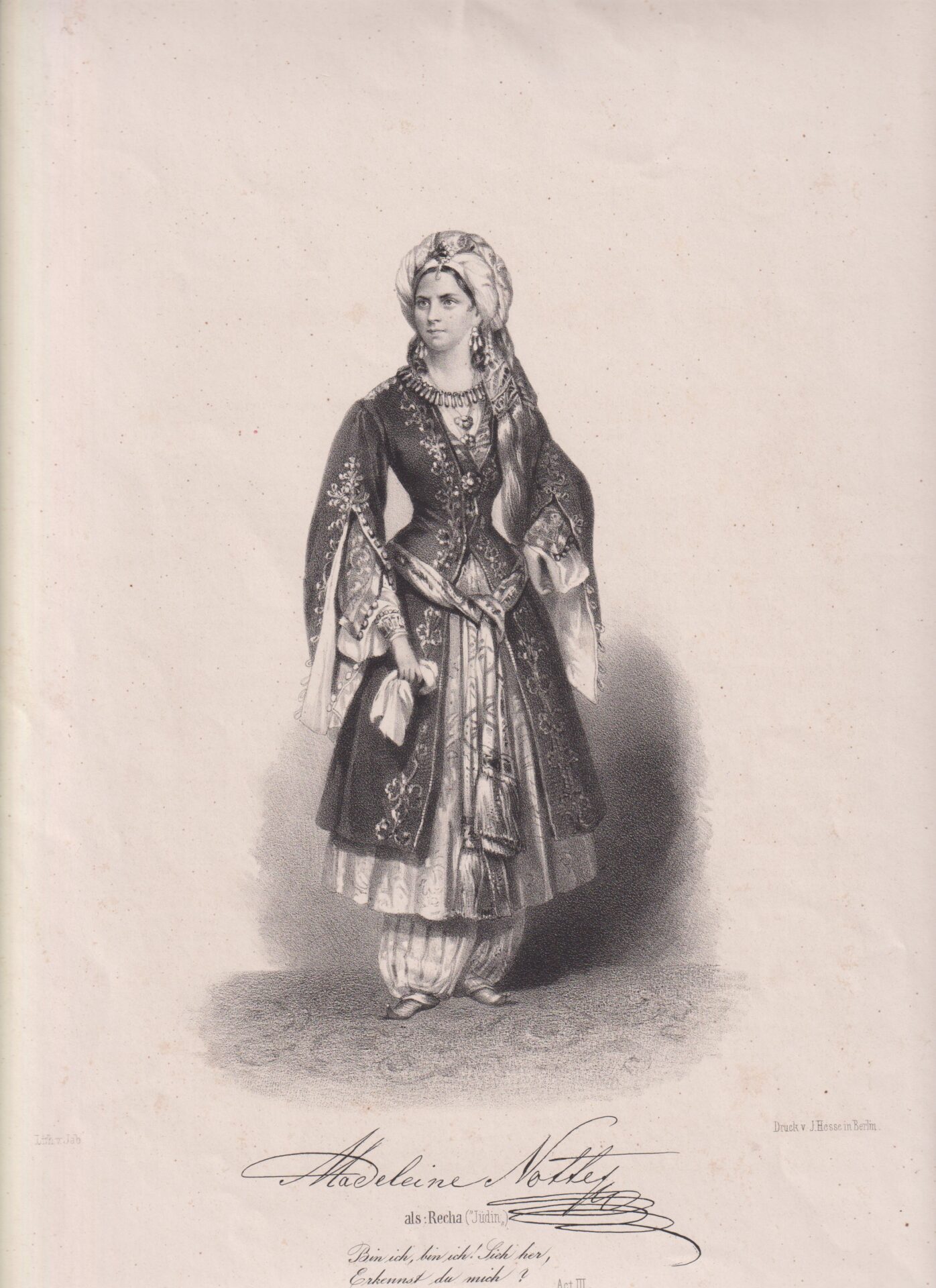

Madeleine Nottes as Recha in Fromental Halévy's Juive, ca. 1850, JMS 2025

Close up of the description of the juive tunic

Journal des Dames, 1803

«Today, we’d call them ‹woke›»

Naomi Lubrich on Historical Fashion Prints

The Jewish Museum of Switzerland collects prints from costume books from the 16th to the 20th centuries. The books depicted various cultural groups in their traditional dress, among them Jews, from Tashkent to Paris. JMS curator Christina Meri spoke to Naomi Lubrich, fashion historian and museum director, about Jewish fashion, medieval doctors, ‹exotic beauty› and a tunic of the French Revolution.

Christina Meri: Naomi, what is so interesting about old fashion plates?

Naomi Lubrich: I’m fascinated by the fact that they are both hardly known and incredibly influential. Fashion images were never considered great art, so they are often overlooked in art history and cultural studies, including Jewish studies. But they had a wide proliferation. Clothing is an easily accessible subject, and fashion books were printed in large numbers, much like fashion magazines today. So they informed our image of cultural groups, among them Jews.

CM: So they are testaments to the past?

NL: You’d be surprised: The old images are still influential today. Costume designers consult old dress books to design clothes for theater and cinema, especially when set in the past. Designers are still copying and adapting the outfits from the old books, again and again.

CM: I can see that the prints are helpful for the stage and screen adaptations, but how are they useful for a museum?

NL: On the one hand, they help us date and locate visual representations, in cases where we have no information. A striking hat, a belt, an unusual shoe can give us clues about where the image might come from. In addition, they provide material for subjects that would otherwise be difficult to illustrate. For example, we have a print from Padua of the year 1593, from Alessandro Fabri’s costume book «Diversarum nationum ornatus et habitus.» The print shows a Jewish doctor from Constantinople. This is relevant to us, because Jewish doctors from around the Mediterranean also provided medical service in Switzerland as early as the 14th century. There are numerous records of Jewish physicians: a doctor named Jocet (Fribourg 1356), Helyas Sabbati from Bologna (Basel 1410), David (Schaffhausen 1535/1536), and Abraham and Samuel (Lucerne 1544/1554). They were coveted workers, while other Jews were banned from the very same cities. We know little more about them than their first names and the places they worked. So the drawing provides us valuable visual material. The fashion illustration shows us how widely known Jewish doctors were, and how people imagined them to look like. The clothes, however, were likely fictitious.

CM: What other questions do the fashion images answer?

NL: For instance, they can answer questions about religious clothing. Let’s take the perennial topic of head coverings. Jewish head covering is comparably recent. In Roman times, Jews did not wear head coverings – or any other special garments, for that matter. Historians agree on this, because Roman writers observed Jews in detail – and often made fun of them; but they recorded nothing about their appearance. It was probably not until the Middle Ages that Jewish men purposefully covered their heads when praying. Until the 20th century, they would wear their best hats. In the synagogue paintings by Otto Wyler (St. Gall 1912) and Walter Haymann (Zurich 1960), all the men are wearing top hats. But around 1960, hats went out of fashion. The turning point most often cited is John F. Kennedy’s oath in 1961, which he swore bareheaded. It must have been at this time that the kippah came, in orthodox circles, into constant use, even indoors, because photos of the New York Yeshiva University from 1954 show board members bareheaded. This is surprisingly late. Finding the kippah’s antecedents and tracing its spread reveals the recency of some symbols and practices that we identify with Judaism, as if they had always been there.

CM: Are there any noteworthy images of women?

NL: Sure! There’s the so-called ‹Oriental› beauty, for instance. In the 19th century, artists had a penchant for painting ‹exotic› women, especially Tunisians and Moroccans, wearing draped, gold-covered gowns. A famous example is the dancer in Delacroix’s Noce juive dans le Maroc (1839). Among the prints – and later photographs and postcards – were many Jewish women, as the captions explain. They were both exoticized and eroticized. These fashion images were frequently adapted for theater and opera, for instance Recha, Eleazar’s daughter, in Fromental Halévy’s opera, La Juive. We have a print of the Viennese soprano Madeleine Nottes portraying an ‹orientalized› Recha around 1850. At the time, the image of the ‹Oriental Jewess› inspired sympathy and curiosity for the Jewish world.

CM: So fashion could be political.

NL: Isn’t clothing always political? Let’s take a fashion accessory of the French Revolution, a tunic known as «juive» or «lévite.» Magazines depicted the «Jewish tunic» from 1790 onwards. What was Jewish about it? It had a patterned hem, as in Biblical times, when hems were used as a stamp to convey personalized messages, like a signature. In an illustration in the 1803 Journal des Dames et des Modes, the Jewish tunic was a bold political statement. It wasn’t until 1791, in the wake of the French Revolution, that Jews were granted citizenship and equal rights. In 1806, the Jewish representative body was established, the Sanhedrin, and in 1807 Judaism was recognised as an official religion. For the editors of the ladies’ magazine to recommend their readers to wear a Jewish tunic as early as 1803 can be interpreted as an expression of solidarity with French Jewish women. It was progressive. Today we’d call it ‹woke.›

CM: Naomi, thank you very much!

verfasst am 30.05.2023

Barbara Häne sheds light on a photo album from wartime Switzerland