«Jews have always inhabited the countryside.»

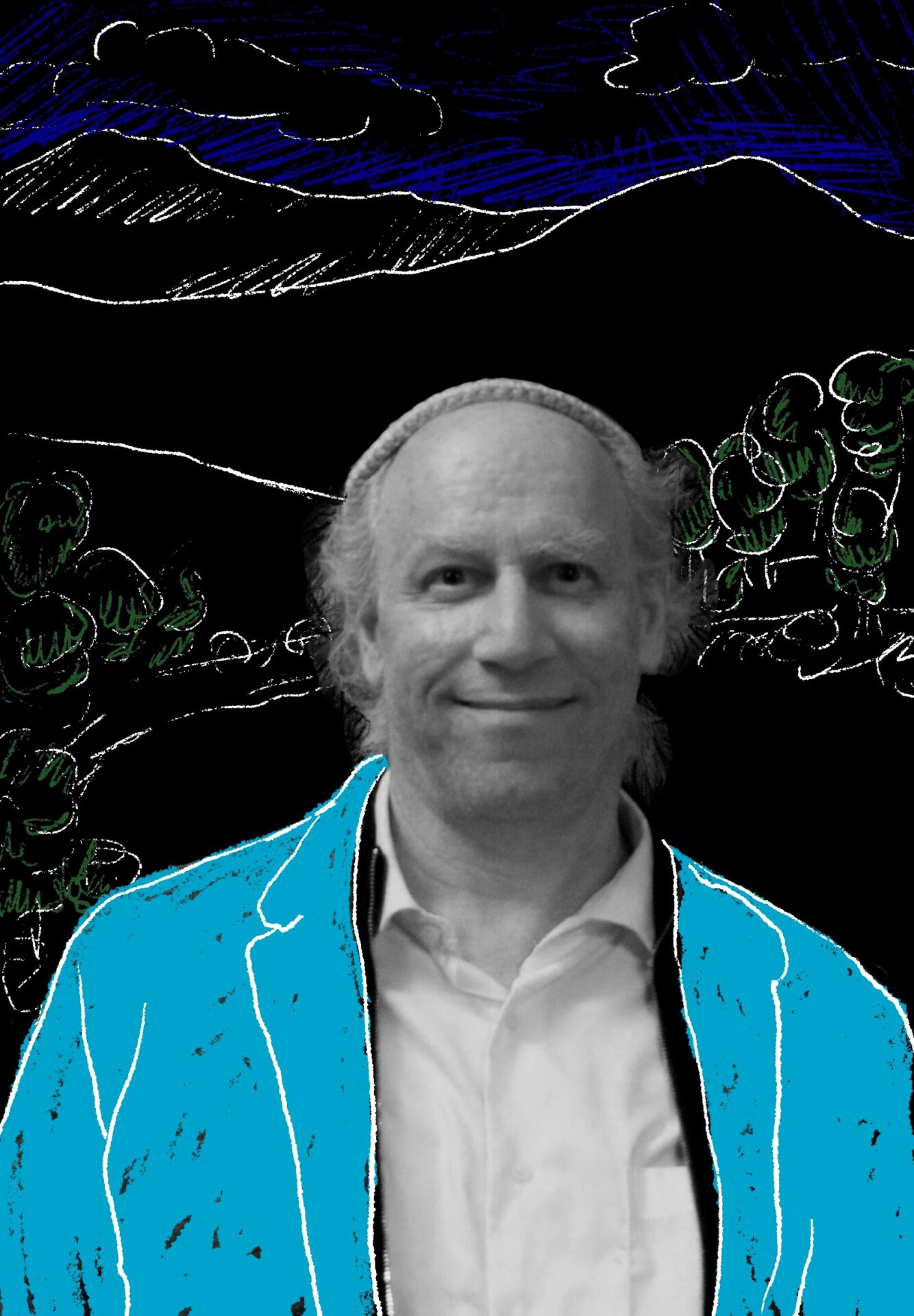

Jonathan Schorsch on Jewish environmentalism

Jonathan Schorsch is a professor of Jewish religious and intellectual history at the University of Potsdam and director of the Green Sabbath Project. Together with Dr. Efrat Gilad in Bern and Dr. Netta Cohen in Oxford, he is establishing Jewish environmental history as a new field of study. Museum director Naomi Lubrich spoke with him about Jewish back-to-nature movements, rural folklore and the cosmic consequences of simple living.

Naomi Lubrich: Jonathan, what led you to study Jewish environmentalism?

Jonathan Schorsch: I’ve always been an environmentally oriented person, but I didn’t begin studying environmentalism professionally until ten years ago, ca. 2013. The reasons were on the one hand my personal life trajectory – I lived in the Bronx, Berkeley, Jerusalem and Berlin in varying proximity to nature – and on the other hand the worsening global news. It’s a field I’m passionate about, and it’s not yet well-trodden.

NL: What can a Jewish perspective contribute to environmental studies?

JS: Judaism developed ritual practices for sustainable living. Jewish ideas about mitzvot, good deeds, overlap considerably with ecological thinking. Both are about living ethically, about regulating our actions, about controlling our food, about managing our personal behavior. Both also have a communal component consisting of policies and laws for society at large. Kabbalistic Judaism contributes a third aspect: It considers our personal impact on our world, the cosmic consequences of our actions.

NL: How far back can you trace Jewish environmentalism?

JS: At least two hundred years. I’m currently studying Joseph Perl from Galicia (1773–1839). He was a maskil, a so-called enlightened Jewish man. His first book, Megalleh Temirim (Revealer of Secrets, 1819), is a scathing attack on Hasidism, and his second book, a novel, Bokhen Tzadik (Searching for the Righteous,1838) sets his protagonist searching for righteous Jews in Poland. He finds none – neither among the enlightened, nor among the religious. He sets off on a journey to rural Crimea, where he finds what he was looking for: Jewish farmers living the redemptive life. The families are self-sustaining. They live simply, and they eat and wear what they produce. They are craftsmen who work with their hands to make what they need. Ideologically, it could have had been written in the 1970s.

NL: It sounds very romantic.

JS: It was! Today, we remember the haskala as a rational movement, but it also borrowed heavily from romanticism. Many of the maskils read Rousseau! More than that, Perl’s cluster of ideas and values is incipient Zionism. Think about the ideas of men with each their own plot of land with their fig tree and vine, a biblical vision refashioned for modernity. For his time, Perl was modern, even cutting-edge.

NL: Did Jewish folklore also find its expression in objects, in design?

JS: That would be something to look out for. I can imagine it did. The shtetls were peri-urban and peri-rural, meaning mixed rural-urban. The Jews shared their daily lives with animals, they went to fields to pick fresh flowers for Shabbat. Many eastern European synagogues feature agricultural motifs in their decoration. Rural Judaism hasn’t been sufficiently studied; scholars have turned much more of their attention to Jews as urban intellectuals. But they have always inhabited the countryside. They were never alienated from nature until quite late in their history.

NL: Certainly not in Switzerland.

JS: No, nor in the Polish shtetls. Small-town life has always smacked of nostalgia. The narrative of disappearing Jewish towns touched the hearts of many urbanites. As the writer and ethnographer An-Ski wrote: Rural lives have always been on the brink of disappearing.

NL: Jonathan, Thank you for your insight.

verfasst am 07.11.2023

Alliya Oppliger looks back at Monumenta Judaica on its 60th anniversary.