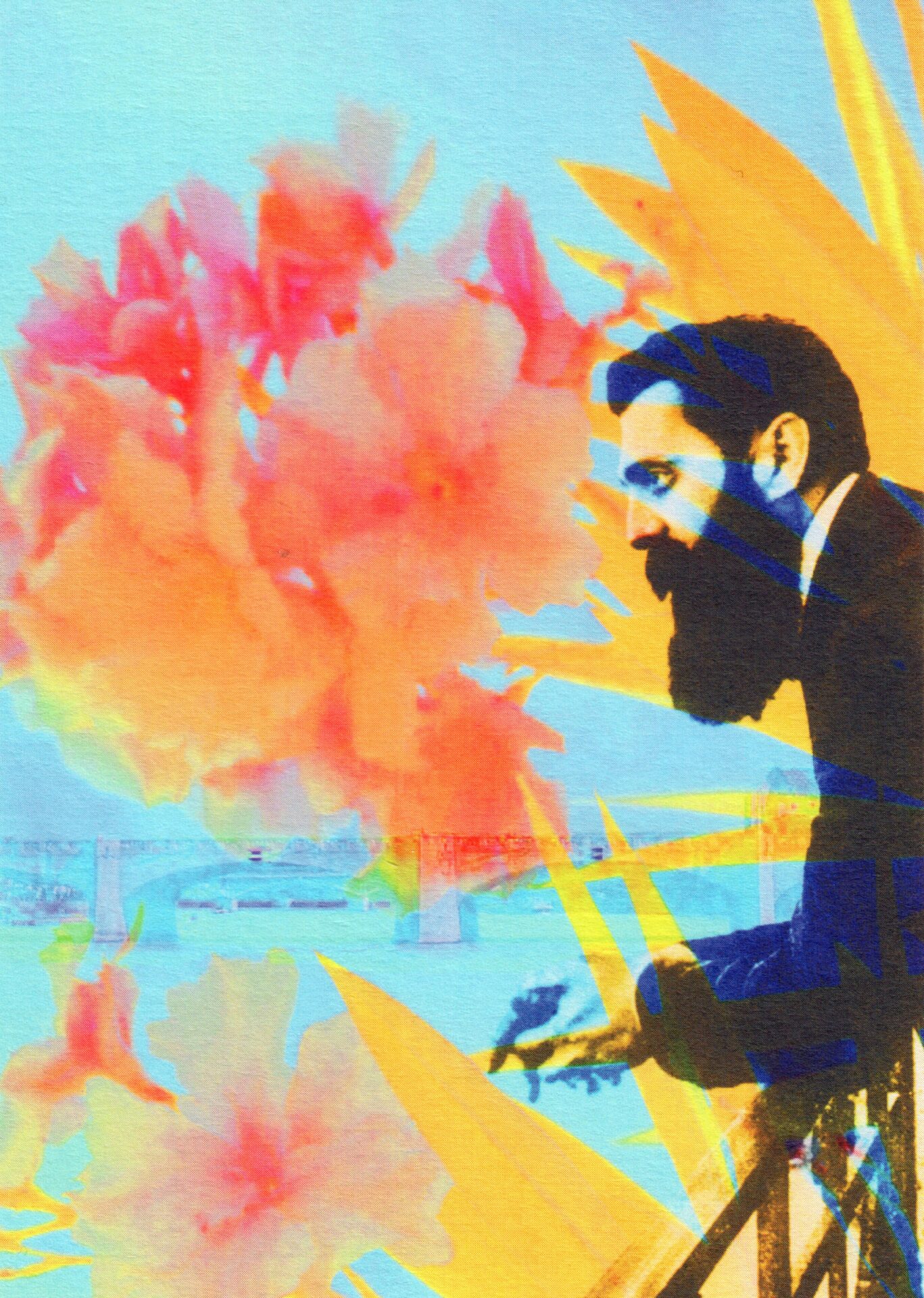

«Herzl appeared on the scene at a moment when many Jews yearned for a charismatic, inspiring leader.»

Five questions for Derek Penslar

This year marks the 125th anniversary of the First Zionist Congress held in Basel. The man who initiated and led the congress was Theodor Herzl, and besides his talent for organizing, his charisma and energy made it a success. Who was the man? Professor Derek J. Penslar of Harvard University wrote a new biography of Theodor Herzl, which appeared this year as «Staatsman ohne Staat» in German. Naomi Lubrich asked Professor Penslar about his research.

Naomi Lubrich: Your book on Theodor Herzl, «Staatsmann ohne Staat,» appeared in German this year as the most recent biography of man who has been studied from many angles. What does your book address that the previous biographies ignored?

Derek Penslar: Previous biographies focused on the construction or deconstruction of myth – presenting Herzl as a larger than life, heroic figure or a troubled, fin de siècle Jewish intellectual struggling to find his place in the world. My biography considers these two approaches to be interdependent: Herzl’s troubled personality, combined with his brilliance, charisma, and organizational ability, made him a great leader. My biography of Herzl also differs from its predecessors by presenting leadership as dialogic, constantly shaping and being shaped by the leader’s followers. Herzl appeared on the scene at a moment when many Jews yearned for a charismatic, inspiring leader untainted by pre-existing and failing Jewish institutions.

NL: You list a number of reasons for Herzl’s success, among them psychological. Herzl was depressed, egocentric, and a workaholic. But the Zionist project helped him find stability. How?

DP: Herzl longed for greatness. At first, he sought it in the theater, but although he was a good playwright, his work was not memorable. Herzl was a gifted journalist, but he did not respect his craft. And during his time as a journalist in Paris Herzl had come to see how corrupt the world of politics could be. Herzl saw Zionism, in contrast, as a pure and noble ideal, to which he could devote his life and upon which he concentrated his psychic energy.

NL: Among the circumstantial reasons for Herzl’s success was the decreasing influence of rabbinic authorities of his time. Herzl didn’t know much about Judaism. What role did Jewish culture play in his vision of a new state?

DP: Herzl did not separate Jewish from European culture. Herzl was not hostile to Hebrew or Yiddish culture, but his Jewishness was that of a cosmopolitan, fin de siècle European, and that cosmopolitan spirit infuses his vision for a future Jewish homeland. In his novel «Altneuland,» he depicts a new Jewish homeland where the Temple has been rebuilt, but in its aesthetic grandeur it resembles a Viennese cathedral. «Altneuland» has European-style opera and theater, but in the novel the opera being performed is based on the life of the 17th-century Jewish false messiah Sabbatai Zevi.

NL: You write that Herzl’s reception during his lifetime was mixed. Which groups opposed him?

DP: Zionism was a minority movement – at the time of Herzl’s death, only about 100,000 Jews – one per cent of world Jewry – had formal Zionist affiliations. Most orthodox Jews considered Zionism blasphemous; many secular Jews in eastern Europe and North America preferred revolutionary socialist movements over Zionism, and assimilationist Jews found Zionism to be at best an embarrassment and at worst a threat to their increasingly comfortable positions in their homelands.

NL: Today, Jewish communities look much different from those of the early 20th century. Would it be conceivable for any one person to be able to unify Jews from ultra-orthodox to egalitarian, the way Herzl unified the diverse groups in his day?

DP: Timing is everything. When Herzl appeared on the scene, a critical mass of Jews needed a leader just like him. Twenty years later, during World War I, Jews desperately needed a consummate diplomat who could imbed Zionism within the post-war order – and Chaim Weizmann rose to greatness. Twenty years after that, Zionism needed a leader who could build a state and army, and Ben-Gurion fulfilled that task. Today, the needs and desires of Zionists throughout the world and Israelis in the Jewish state are so diffuse, so contradictory, that it’s hard to image a single person uniting and fulfilling them.

NL: Thank you very much, Professor Penslar.

verfasst am 09.08.2022