Holy Museology

Religious objects in museological practice

The exhibition «In the Name of the Image» at the Museum Rietberg in Zurich shows concepts of the sacred in Islam and Christianity (February – May 2022). The sacred is a key concept in Judaism as well, and can play a role in museum conservation. Dr. Caroline Widmer, the curator of Indian painting at the Museum Rietberg, asked Dr. Naomi Lubrich about when and how the religious status of an object influences museological practice at the Jewish Museum of Switzerland during the panel discussion «Religious Objects in Schools and Museums» (organized by the Museum Rietberg and the Zurich University Pädagogische Hochschule with Prof. Dr. Eva Ebel, Unterstrass Zurich, Prof. Dr. Edith Franke, University of Marburg, and Léa Burger, SRF).

CW: What is considered a religious object within the Jewish Museum’s collection?

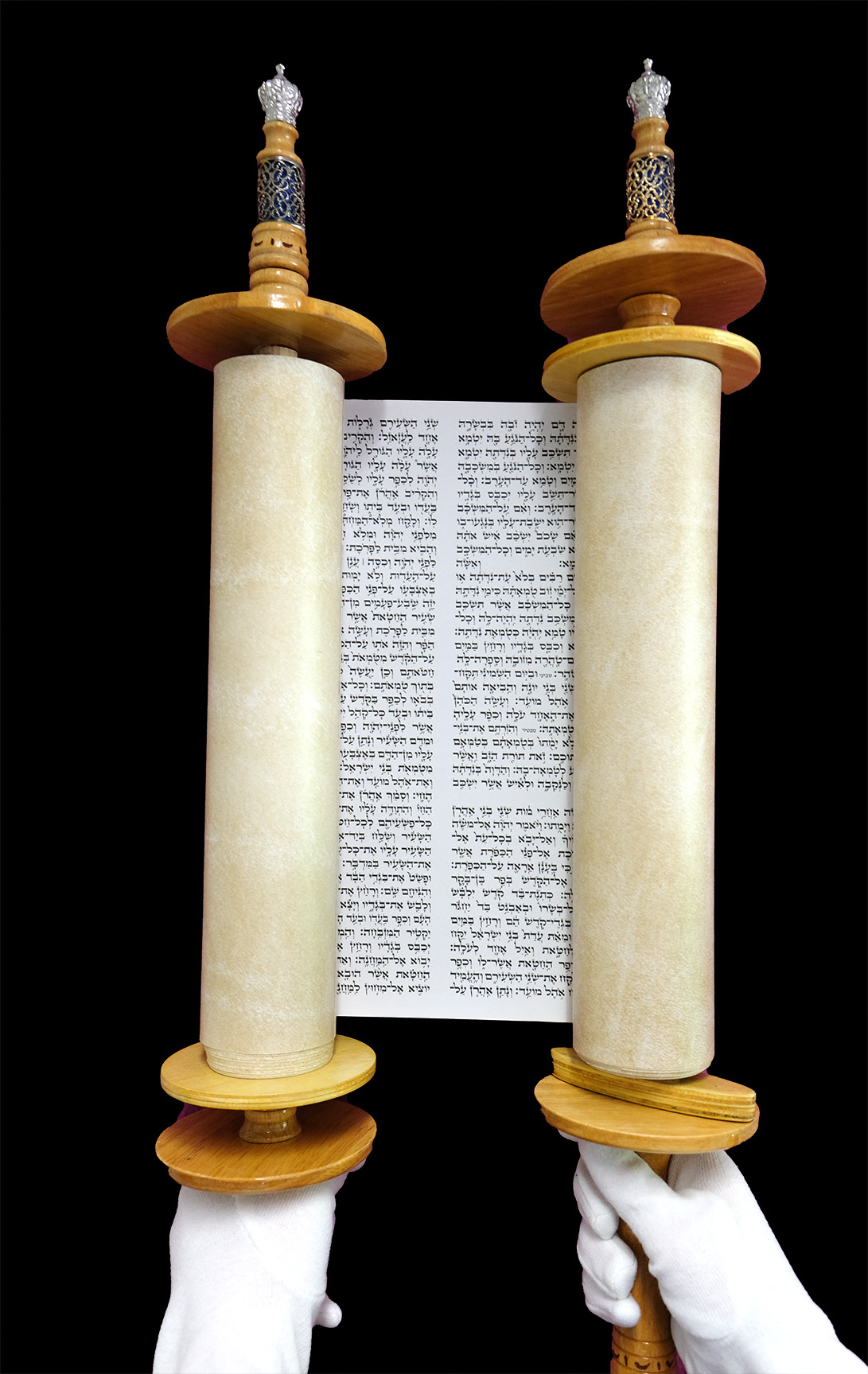

NL: Most of our objects are religious. Anything that is used in ritual would fall in the category «religious object», for instance a kippah, a spice box, and even a candle, depending on the context. But religious is not the same as sacred. In Judaism, objects that contain the name of God are sacred, above all, the Torah. And since the name of God is sacred, any object that has touched the Torah is sacred, for example mappot, Torah binders, and me’ilim, Torah mantles.

CW: Are there any regulations as to the handling of sacred objects?

NL: Oh yes! Let me give you some examples: No one should touch the writing on the Torah with their bare hands. No one should say the name of God out loud outside of worship. Books and any other object which contains the name of God may not be disposed of or destroyed. Incidentally, this requirement has been of great benefit to Jewish material history, because discarded objects have survived in genizot, which are storage rooms, sometimes for centuries. Today many of these stored objects are testimonies of a Jewish history which might otherwise be forgotten. If they cannot be stored, sacred objects can be buried – like people. The photographer Fred Stein documented a famous burial of Torah scrolls in 1952 at the Beth El Cemetery in Paramus, New Jersey, in which Salo Baron and members of the Synagogue Council of America carried a number of scrolls wrapped in tallitot, prayer shawls, to lay them to rest.

CW: For which reasons would a Torah scroll be retired from use?

NL: A Torah scroll that has faded, is torn or has fallen down would no longer be used during service. Nor can a Torah scroll be used if it has an error in the text. The Torah must be flawless, in which case it is considered «kosher.» If a damaged Torah cannot be saved, it would need to be buried. But in many cases, the scroll can be repaired. Some Torah scribes devote much effort to repair «non-kosher» Torah scrolls. They mend cracks, fix mistakes, and reinscribe faded areas to make them suitable for service. The Scrolls Memorial Trust in London, for example, restored over 1,500 Torah scrolls from the Czech Republic which had been damaged during the Shoah. Once repaired, they were donated to congregations in need of Torot.

CW: What about the Jewish Museum? What would you do with a non-kosher Torah scroll?

NL: For us, whether an object is kosher or not irrelevant. We take great pleasure in preserving and researching ancient objects that have a long and circuitous history. For example, one Torah scroll in our exhibition dates back to Cairo of the fourteenth century. August Johann Buxtorf probably bought it in Marseille around 1720, and after he returned to Basel, he and several scholars used it at Basel university to study Hebrew. Thereafter, it was donated to the university library, in whose possession it is today. For us, the Torah scroll is evidence of the transfer of knowledge between North Africa, Southern France and the Old Confederation at a time when Jews were not allowed to live in Basel. The fact that the ink has partly faded and the leather is no longer fresh does not weaken its aura – quite the opposite.

CW: And how would the museum dispose of a sacred object?

NL: Luckily, we haven’t needed to deaccession a sacred object yet! But hypothetically speaking, we would first offer the object to a Jewish community or discuss the possibility of restoring it with a scribe, sofer. This is usually less expensive than writing a new scroll, which is a big investment.

CW: How is your handling of sacred objects different from their handling in religious services?

NL: Well, for one, we only touch our Torah scrolls with gloves so that the parchment does not suffer from the sweat and dirt on our skin. And whereas certain orthodox conservative congregations do not allow women to touch the Torah scroll, we are gender equal. Our only worry is that whoever lifts the Torah be strong, because Torah scrolls are very heavy!

CW: Thank you very much!

verfasst am 31.05.2022

© Photograph by Fred Stein, collection of the American Jewish Historical Society, New York, USA.